The Real Stigma Of Substance Use Disorders & Surrounding Misinformation That Effects Their Recovery

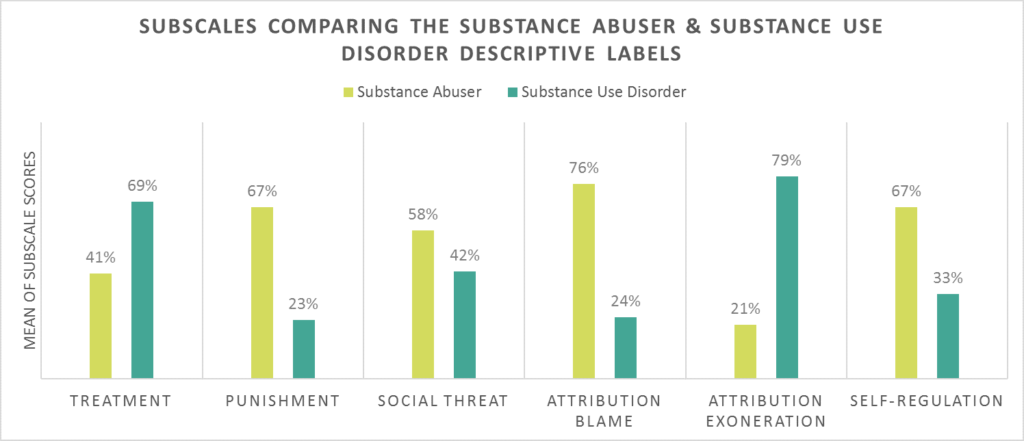

The Recovery Research Institute conducted a study, asking “Does it Matter How We Talk About People with Substance Use Disorder?” These are the results below.

Stigma is an attribute, behaviour, or condition that is socially discrediting.

Recovery Research Institute

What Problem Does This Study Address?

Illicit drug use disorder is the most stigmatised health condition in the world, with alcohol use disorder not far behind at fourth in the world, among a list of 18 of the most stigmatised conditions internationally. Importantly, degree of stigma is related to the perceived cause of the condition (if perceived not to be someone’s fault, stigma is lower) and perceived control over the condition (if perceived not to be under someone’s control, stigma is lower).

In this study, Kelly and colleagues were interested in whether the language we use to describe individuals with substance-related problems may evoke different types of stigmatising attitudes. The terms used to describe individuals suffering from substance-related conditions may convey different attributions their perceived cause and controllability.

More specifically, study authors tested whether describing someone as a “substance abuser” increases the likelihood of evoking more punitive attitudes, than describing the same person as having a “substance use disorder”. The term “abuse” may convey the notion that the person has control (one of the two factors associated with stigma) and therefore is engaging in wilful misconduct. The term “disorder”, on the other hand, may convey the notion that there is some kind of medical malfunction at play, increasing the likelihood of evoking more therapeutic attitudes and welcoming attitudes and support towards recovery.

How Was This Study Conducted?

In a survey, 314 individuals responded to 35 questions related to how they perceived or felt about two people “actively using drugs and alcohol”. One person was referred to as a “substance abuser”, and the other was referred to as “having a substance use disorder”. No further information was given about these hypothetical individuals.

The 35 item survey questions used the stem “Which of these two individuals…” & covered the following areas:

- Treatment (example: “…would you be more likely to recommend treatment to decrease substance use?”)

- Punishment (example: “…would you be more likely to recommend punishment to decrease substance use?”)

- Social Threat (example: “…would do something violent to others?”)

- Causal Attribution – Blame (example: “…has a problem caused by his own choices?”)

- Causal Attribution – Exoneration (example: “…has a problem that is more likely inherited?”)

- Self-Regulation (example: “…is able to overcome his problem without professional help?”)

Half (50%) of participants worked in the healthcare field, while 20% were students, 29% worked outside healthcare or were unemployed or retired, and 5% did not report an occupation. They were 31 years old, on average (ranging from 17 to 68 years old), 81% were White, 76% were female, and half had a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education.

What Did This Study Find?

Participants felt, overall, that the “substance abuser” was:

- Less likely to benefit from treatment

- more likely to benefit from punishment

- More likely to be socially threatening

- More likely to be blamed for their substance related difficulties and less likely that their problem was the result of an innate dysfunction over which they had no control

- That they were more able to control their substance use without help

All of these differences were large in magnitude, apart from their greater level of social threat which was a medium sized difference.

In the figure below from the study, the values represent the average response rate to items making up that scale. So if the scale value is closer to 100%, participants chose that individual (“substance abuser” or “having a substance use disorder”) more often in response to items on the scale. Although the questionnaire asked participants specifically to choose one individual or the other, they were able to choose both, or could have chosen neither individual, so the values for each stigma domain do not necessarily add to 100%.

(Kelly, Dow & Westerhoff, 2010)

In contextualising the importance of this work, another related study is important to mention, also by Kelly and colleagues. In that study, mental health clinicians (two thirds of whom had a doctoral level degree) were randomised to receive just one of two vignettes about an individual with substance-related difficulties. The vignettes were identical except – like the study reviewed here – in one vignette, the individual was referred to as a “substance abuser” and, in the other, as “having a substance use disorder”. The questions that followed exposure to the vignette were similar to this study, though not exactly the same and instead of choosing one hypothetical individual or another, they simply responded about their level of agreement regarding statements presented to them about the person in the vignette. For these clinicians, compared to those in the “substance use disorder” group, those in the “substance abuser” group felt the individual was more to be blamed for his problem and more in need of punishment to make a change in his substance use (e.g., “He could have avoided using alcohol and drugs” and “He should be given some kind of jail sentence to serve as a wake-up call”).

There were no differences between groups in the perception of the individual as a social threat or whether or not the individual could not control his difficulties and would benefit from treatment. Overall, then, trained mental health clinicians are less vulnerable to language-influenced perceptions of individuals with substance-related problems than individuals outside the mental health field. They are not completely immune, however, from the role language plays in how we perceive individuals with health conditions – substance-related health conditions in this case.

To Briefly Summarise:

Results: No differences were detected between groups on the social threat or victim-treatment subscales. However, a difference was detected on the perpetrator-punishment scale. Compared to those in the “substance use disorder” condition, those in the “substance abuser” condition agreed more with the notion that the character was personally culpable and that punitive measures should be taken.

Conclusions: Even among highly trained mental health professionals, exposure to these two commonly used terms evokes systematically different judgments. The commonly used “substance abuser” term may perpetuate stigmatizing attitudes.

Taken together, these two studies are important in understanding how language may influence perceptions and perpetuate stigma.

Why Is This Study Important?

It may be that exposure to the term “substance abuser” elicits a more punitive implicit cognitive bias whereas the term “substance use disorder” elicits a more therapeutic attitude. Use of the “substance use disorder” term may be preferable as it may be less stigmatising. Given the common use of the “abuser” term among clinicians, scientists, policy makers, and the general public, this term may be a part of the reason why individuals seek or remain in addiction treatment.

For example, in a large, representative sample of individuals with alcohol use disorder, those who felt alcohol-related problems were highly stigmatised conditions by people they knew in their day-to-day lives were less likely to seek treatment, while those who felt alcohol-related problems were less stigmatised by these people were more likely to seek treatment. One reasonable hypothesis, then, is that if as a society, we can begin to address the stigma of substance use disorder, we can help increase rates of treatment seeking. Changing our language by dropping the term “abuser” and adopting terminology more consistent with a medical and public health approach may be one way to do this.

Overall, these studies are part of a body of literature that is helping to spur change in how language is used in the field. Recently, the International Society of Addiction Journal Editors, based in large part on these studies, provided guidance strongly cautioning against use of the term “abuse”, and advocated instead for either substance use disorder (if substance use meets diagnostic thresholds) or several variations on substance use that may cause harm, such as hazardous substance use or harmful substance use.

Limitations

- Individuals were not randomly assigned to receive one term or another. However, as mentioned earlier, a study with a large sample of more than 500 clinicians showed that negative perceptions of “substance abusers” remain even when a randomised trial is used.

- Also, these surveys ask individuals to respond to hypothetical individuals and scenarios. While this is a common strategy in stigma-related research, participants might not respond to people in their real lives in the same way they do on the survey.

Next Steps

There are several next possible steps related to research on stigma and substance use disorder, including but not limited to the following three areas:

- First, researchers might investigate stigma related to other types of language that are considered common parlance in the world of addiction treatment and recovery, such as “addict” and “alcoholic”, as well as “clean” versus “dirty” when speaking about results of individuals’ toxicology screens.

- Second, studies might engage people in role-plays with actors portraying individuals with substance-related problems, and observe and record their actual response.

- Finally, much work is needed to understand how to reduce stigma associated with substance use disorder. Fortunately, there has been work on stigma reduction for other health conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, and researchers may be able to build on this work and apply it to substance use disorder.

The Bottom Line

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Language matters. This study suggests that the words “abuser” and “abuse” can evoke automatic negative thoughts about individuals with substance-related problems. The Recovery Research Institute “Addiction-ary” can help provide ideas on terms that are less stigmatizing. With less stigma surrounding alcohol and other drug use disorders, individuals with these conditions may be more likely to seek help, stay in treatment, and achieve long-term remission

- For scientists: This research provides important evidence cautioning against the use of “abuser” and “abuse” terminology on which to build. Given the methodological limitations of this study, there are several ways in which researchers can help grow this important area of substance use disorder research. Some ideas are provided in “What are the next steps in this line of research” above.

- For policy makers & Government: Language matters. This study suggests that the words “abuser” and “abuse” can evoke automatic negative thoughts about individuals with substance related problems. Less stigma surrounding alcohol and other drug use disorders, individuals with these conditions may be more likely to seek help. In a related sense, experts have used these types of studies in support of a public health, rather than a criminal justice, approach to addressing societal harms related to substance use disorders.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Language matters. This study suggests that the words “abuser” and “abuse” can evoke automatic negative thoughts about individuals with substance-related problems, even among individuals working in the health care field. The Recovery Research Institute “Addiction-ary” can help provide ideas on terms that are less stigmatising. With less stigma surrounding alcohol and other drug use disorders, individuals with these conditions may be more likely to seek treatment.

You can help reverse the harmful stereotypes about addiction by improving access to care, supporting people affected by this disease and change the words we use when discussing this health condition

Language

Consider using these recommended terms to reduce the stigma and negative bias when talking about addiction, treatment or awareness.

| Instead of… | Use… | Because… |

|---|---|---|

| Addict User Substance or drug abuser Junkie Alcoholic Drunk Former addict Reformed addict | Person with substance use disorder Person with opioid use disorder (OUD) or person with opioid addiction [when substance in use is opioids]Patient Person with alcohol use disorder Person who misuses alcohol/engages in unhealthy/hazardous alcohol use Person in recovery or long-term recovery/person who previously used drugs | Person-first language. The change shows that a person “has” a problem, rather than “is” the problem. The terms avoid elicit negative associations, punitive attitudes, and individual blame. |

| Habit | Substance use disorder Drug addiction | Inaccurately implies that a person is choosing to use substances or can choose to stop. “Habit” may undermine the seriousness of the disease. |

| Abuse | For illicit drugs: Use For prescription medications: Misuse, used other than prescribed | The term “abuse” was found to have a high association with negative judgments and punishment. Legitimate use of prescription medications is limited to their use as prescribed by the person to whom they are prescribed. Consumption outside these parameters is misuse. |

| Opioid substitution Replacement therapy | Opioid agonist therapy Medication treatment for OUD Pharmacotherapy | It is a misconception that medications merely “substitute” one drug or “one addiction” for another. |

| Clean | For toxicology screen results: Testing negative For non-toxicology purposes: Being in remission or recovery Abstinent from drugs Not drinking or taking drugs Not currently or actively using drugs | Use clinically accurate, non-stigmatising terminology the same way it would be used for other medical conditions. Set an example with your own language when treating patients who might use stigmatising slang. Use of such terms may evoke negative and punitive implicit cognitions. |

| Dirty | For toxicology screen results: Testing positive For non-toxicology purposes: Person who uses drugs | Use clinically accurate, non-stigmatising terminology the same way it would be used for other medical conditions. May decrease patients’ sense of hope and self-efficacy for change. |

| Addicted baby | Baby born to mother who used drugs while pregnant Baby with signs of withdrawal from prenatal drug exposure Baby with neonatal opioid withdrawal/neonatal abstinence syndrome Newborn exposed to substances | Babies cannot be born with addiction because addiction is a behavioural disorder—they are simply born manifesting a withdrawal syndrome. Use clinically accurate, non-stigmatising terminology the same way it would be used for other medical conditions. Using person-first language can reduce stigma. |

It starts with something that seems small, but actually makes a huge difference: the words and language we use to talk about addiction.

How Our Definition Of Recovery Has Changed Over Time

Addiction has no boundaries. Addiction does not discriminate. It’s a disease, but it’s a treatable, medical disease

Person-First Language Is Proven To Reduce Stigma & Improve Treatment Outcomes

It’s not about being sensitive, polite or politically correct. It’s about access to quality treatment and care.

Person-first language doesn’t define a person based on any medical disorder he/she may have. It’s non-judgmental, it’s neutral and the diagnosis is purely clinical.

| Words To Avoid Using | Words To Use Instead |

| Addict | Person with substance use disorder |

| Alcoholic | Person with alcohol use disorder |

| Drug problem, drug habit | Substance use disorder |

| Drug abuse | Drug misuse, harmful use |

| Drug abuser | Person with substance use disorder |

| Clean | Abstinent, not actively using |

| Dirty | Actively using |

| A clean drug screen | Testing negative for substance use |

| A dirty drug screen | Testing positive for substance use |

| Former/reformed addict/alcoholic | Person in recovery, person in long-term recovery |

| Opioid replacement, methadone maintenance | Medications for addiction treatment |

By using person-first language like this, we can make great progress toward reducing the deadly stigma associated with addiction.

Of the 709 survey respondents:

- 62% would work with someone with a mental illness

- 22% would work with someone with a substance use disorder

- 64% believed employers should be able to deny employment to people affected by addiction

- 25% believed employers should be able to deny employment to those affected by a mental illness

- 43% opposed giving individuals with substance use disorders the same health insurance benefits granted to otherwise healthy individuals

- 21% opposed giving those with mental illness the same health insurance benefits given to otherwise healthy individuals

37% of college students avoided seeking help for addiction because they feared social stigma

What Are The Effects Of Stigma?

Stigmatisation is one of the most formidable obstacles to an effective mental health/addiction system, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Misconceptions about substance use lead to major health care issues.

Several studies have indicated that stigma is one of the main reasons people avoid treatment. A 2007 study by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse found that 37% of college students avoided seeking help for addiction because they feared social stigma.

Stigma can also make addiction worse. A 2014 study published in the Journal of Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research found that when people with substance use disorders perceived social rejection or discrimination, it increased their feelings of depression or anxiety. Alternatively, people with co-occurring substance use and mood disorders perceived more negative attitudes against them.

Health care providers are wary of stigmatising their patients, too. The authors of a 2008 article published in the Journal of Alcohol Research described how health practitioners avoided using the term “addiction” because they didn’t want to stigmatise their patients. The authors also argued that the term “alcoholism” had been so widely used that belief in the severity of the illness had been weakened.

Naloxone offers a prime example of how stigma can negatively affect health care. One barrier to widespread access to the medication, which reverses the effects of an opioid overdose and has saved thousands of lives, was the stigma around the word “overdose.” Doctors believed patients would worry that the doctor didn’t trust them or considered them an addict if they prescribed it or if someone else found it, they may stigmatise them for carrying Naloxone, discover they have an addiction, so they don’t carry it with them when they should due to fear or risk of discovery, shame, embarrassment or being discriminated against, should their addiction be revealed to those who they may not have wanted to know.

So… Why Is Addiction Stigmatised?

There are several reasons why addiction and those with a substance addiction are stigmatised against. As with many other health conditions throughout history, people feared what they didn’t understand. Not having full control of one’s mind can be scary.

As research, evidence and understanding around addiction grows further, society seems to be slowly overcoming its fear of many mental health conditions. It doesn’t seem to be accepting truths about addiction as quickly, though. The reasons could stem from public policy and decades of anti-drug messages from the government.

Criminalisation

Laws and the idea of criminal behaviour were born from the idea that people who committed certain immoral acts should be punished. For example, theft, murder and rape are almost universally considered immoral, criminal acts.

At present, carrying drugs, selling drugs, transporting drugs and storing drugs is illegal in the UK. This method of managing drug use does not work and has not worked, yet at present, more often than not, the general public still think that they should be punished for a moral failing or because they chose to use.

When countries began passing anti-drug legislation, they sent the message that using drugs was immoral. Soon, illicit drugs became associated with other forms of criminal activity such as violence, drug trafficking and prostitution. It’s easy to see how society associated drug use as a choice and as immoral behaviour.

Addiction in the past also wasn’t as blatant as it is today. People didn’t openly talk about this issue and anyone with an addiction would fear telling anyone due to the heightened levels of discrimination they would receive.

At one point, drinking beer or alcohol was the only way to drink as “drinking water” was contaminated with bacteria, dirt and germs so beer and other associated types of alcohol was all that was easily available. This acceptance to drink alcohol throughout the day meant that those with addictions to alcohol could keep their addiction to themselves and not need to seek help.

Though trying a drug for the first time may be a choice for most people, compulsively abusing drugs despite negative consequences is not a choice for people with substance use disorders. Research indicates that the disease physically and chemically changes the brain, causing cravings and compulsive behaviours.

Even when people recover from addiction or maintain long periods of abstinence/sobriety, anti-drug laws make it difficult for them to reintegrate into society. It can be hard for people with drug convictions to find jobs, get licenses, receive welfare benefits, support children, get permanent housing or accommodation, and many others. Thus, many of the things necessary to increase the chances of long-term recovery are difficult for them to obtain initially in certain cases. This is when their motivation diminishes and they relapse rather than carry on in recovery.

Relapse

Substance use disorders are hard to understand. Many people consume substances of “abuse” would stop when faced with health, social or legal consequences. However, people with addictions are influenced by genetic, environmental, developmental factors as well as physical and mental health conditions. This is why addicts find leaving their substances behind and moving on in recovery, so difficult to stop and maintain without professional help and support.

Stopping seems like an easy solution, but it can be tough for many people with SUD’s.

People in recovery are also judged by high rates of relapse because the public doesn’t understand the disease model of addiction. Other chronic health conditions, such as diabetes and high blood pressure, have high rates of relapse. But society doesn’t shame a person with high blood pressure for eating french fries or a person with diabetes for having an occasional candy bar.

Language

So many words associated with addiction are stigmatising that it can be difficult to determine how to refer to people with substance use disorders. But using stigmatising language can prevent people who need treatment from seeking help and unfortunately, often costs people their lives, as they didn’t seek or received help sooner.

A 2010 study published in the International Journal on Drug Policy found that referring to an individual as a “substance abuser” or as having a “substance use disorder” evoked different judgments among mental health professionals. Even among trained professionals, respondents perceived people who were referred to as substance abusers to be guilty of drug abuse and believed that punitive measures should be taken.

To provide guidance on communicating effectively, the Office of National Drug Control Policy released in 2015 a draft of preferred language for referring to addiction-related terms. You can download this 73 page PDF document from our downloads & media page.

Reducing Stigma

It isn’t easy to reduce stigma associated with addiction because authoritative sources have endorsed misconceptions, myths, misinformation and prejudice for generations. However, society must start to adapt and become more socially inclusive if people with all types of physical and mental health conditions are to get the help they need and deserve.

People with substance use disorders and people in recovery are more likely to seek substance abuse treatment and maintain abstinence/sobriety when they develop social connections. Isolation, discrimination and prejudice are obstacles to social inclusion and will only delay or stop access to treatment and at worst, die.

You can contribute to reducing stigma and promoting social inclusion by:

- Treating people affected by addiction with respect

- Learn about the science of mental health conditions & addiction with up to date facts and information

- Correcting others who have misconceptions, misinformation, discrimination or bullying other because of substance use disorders and mental illnesses

- Supporting resources for people affected by mental illnesses and addictions

Successful stigma reduction initiatives require manpower, money, time and effort. However, you can effectively reduce stigma in your community by implementing social marketing strategies.

According to SAMHSA, stigma reduction strategies can include:

- Education

- Contact with mental health & addiction consumers

- Rewards for positive depictions of people with mental health challenges and addictions

- Praise for those who actively work to change these negative perceptions and stigmas

SAMHSA provides a comprehensive, detailed brochure for developing a stigma reduction initiative. However, you can develop a simple initiative by creating public service announcements for use in newspapers, magazines, on the radio and the internet. You can also create presentations and host workshops on the negative effects of stigma and how to combat it.

Stigma creates shame and guilt, which lead to isolation. Eliminating stigma, prejudice and discrimination against people with substance use disorders are crucial to helping them recover.

For decades, addiction has been characterized by images of graffiti-painted highway overpasses and alleyways strewn with discarded needles, drawing the line between those suffering from addiction and the “rest of us.”

But now, in the midst of an ever-growing addiction pandemic, overdose occupies the top spot for leading cause of accidental death in the United Kingdom, There were 4,359 deaths related to drug poisoning registered in England and Wales alone. This doesn’t include alcohol or statistics in Scotland or Northern Ireland. This number is ever increasing, with approximately 16% increase each year. News stories of the alarming rise in the number of overdose deaths splash across television and newspaper headlines daily. We find ourselves replaced with a new reality, that individuals suffering from substance use disorder are no longer unrelatable strangers, they are our neighbours, our friends, colleagues, community members and most importantly, our family members.

Despite this, new stories continue to rely on click-bait tactics to attract people to their sites; tactics which serve to alienate and de-humanise those suffering from addiction, inducing fear of addicted persons in readers. Instead of contributing to the solution, click-bait tactics can actually increase stigmatisation, which in turn can serve as a barrier to those seeking help for a substance use disorder. The language we use matters, especially when we are talking about an already highly-stigmatised condition such as addiction.

Correctly talking about addiction means omitting sensationalism for more accurate narratives, avoiding stigmatising language, acknowledging evidence-based solutions, and working to give faces and names to the vast number of fathers, mothers, sisters, cousins, friends and neighbours affected by this ever increasing sweeping public health crisis.

12 Simple Tips To Talk, Write & Report About Addiction

- Use Comparable Medical Terminology Whenever Possible: Use substance use disorder (or opioid use disorder, alcohol use disorder, etc.) over “substance abuse.” Someone in treatment is a patient suffering from a health condition. Talk about substance use disorders, and treat addiction the same way you would other chronic medical conditions such as diabetes or cancer in your articles.

- Use Person-first Language: Structure your sentences to put the person first and the disease second. Do not use terms like drug abuser, junkie, addict, alcoholic, or bulimic. Instead, describe the person as an individual with, or suffering from, a substance (opioid/alcohol/cocaine etc.) use disorder. Person-first language articulates that the disease is a secondary attribute and not the primary characteristic of the individual’s identity.

- Avoid Using Stigmatising Terms: Stigma is a known primary barrier for individuals seeking treatment and support for their addiction and recovery, so avoid these terms that are associated with increasing stigma:

- Abuse/abuser—Instead of saying “substance abuse” which has been found in research to even have an effect on the attitudes of healthcare providers regarding evoking more blaming and punitive attitudes, use the word “substance use/misuse” or “substance use disorder”). We refer to people with eating-related problems as having or suffering from an “eating disorder” never as “food abusers”; so do the same for substance use disorders.

- Clean/Dirty—Instead of stating the person is clean or dirty, say that the individual is in remission or recovery, or still has/is suffering from a substance/opioid/alcohol/cocaine etc, use disorder. In the case of toxicology screens, describe the drug screen results as either “positive” or “negative” for particular substances).

- Rehab—Instead, say “residential treatment facility” or “addiction treatment facility.”

- Enabling—Remove fault and intention, instead explaining that “loved ones can unconsciously reinforce substance use.”

- Relapse/Lapse/Slip—Instead say “recurrence of symptoms” or “recurrence of the disorder”

- Opioid Replacement Therapy/Medication Assisted Treatment—Instead say “medication”.

- Share the Solutions That Exist: Substance use disorder is actually a good prognosis disorder, in that the majority of patients fully recover, go on to lead normal lives, and often achieve enhanced levels of functioning. Myriad treatments, resources, and services exist to support recovery. You can also find more help on the Drink ‘n’ Drugs articles and on our help and support page.

- Provide Details of Those Solutions: Include detailed accounts of how people are responding to their substance use disorder problems with actual effective evidence-based solutions (not good intentions) in meaningful detail. Discuss barriers to, or limitations of, the solution and provide detail on how others could implement and replicate the solutions. When possible, avoid what is known as the literary afterthought: i.e, a paragraph or sound bite at the end of an article on the problem(s) of addiction that gives lip service to efforts at solving the problem but the solutions aren’t considered with real seriousness.

- Humanise the Conditions: Use language that is relatable and works to humanise and personalise the condition, avoiding fear and blame tactics that treat those suffering as alien otherness or those people. There were 268,390 adults in contact with drug and alcohol services in 2017 to 2018, which is a 4% reduction from the previous year (279,793). The number of people receiving treatment for alcohol alone decreased the most since last year falling by 6%, (80,454 to 75,787) and by 17% from the peak of 91,651 in 2013 to 2014., it is important not to leave the humanity of those affected. It is difficult to get an actual overall number of those with an SUD or AUD as unless they come forward and enter treatment, it is difficult to apply a number to the picture UK wide.

- Use reliable, up to date, evidence, statistics & sources: Look at the financial interests and place of employment of your sources. Try to identify potential biases in your source materials and provide a variety of voices from across the advocacy, research, medical, and recovery communities. Ensure that you use the latest, most up to date information and resources possible and from reliable, proven and trustworthy sources. No body can argue with facts, statistics and clinical findings from research and experimentation. This will help strengthen your cause.

- Communicate information about the many different pathways to recovery: There are many factions that trumpet specific pathways. Be aware of these different camps and biases and understand that everyone’s recovery may look different, and that is OK. Everyone’s experiences are unique, what works for one person may not work for another. There are many different pathways to abstinence and recovery. We believe the mantra should be “recovery by all and any means necessary”. Information about different options such as community based drug and alcohol services or inpatient style residential rehabilitation facilities provide opportunities for those with SUD’s/AUD’s to decide what is best for them.

- Give the 30,000-foot View: Substance use disorders are a chronic disease, not an acute condition. The brain takes years to recover, and it can take many different types of treatments and multiple years for some people to achieve full and lasting abstinence and sobriety. Don’t blame the individual when they are not able to successfully recover as quickly as you may like them to, or because their Doctor’s aren’t able to successfully ‘cure’ the person in a 30-day addiction treatment program using acute care models. Zoom out and contextualise the condition, giving a 30,000-foot view, that recovery can take time to achieve, but is infinitely worth the pain, hardship, effort and dedication it can require. And know that most people will eventually recover.

- Be Respectful & Supportive: Despite being a good prognosis disorder, it is important to also acknowledge that premature mortality rates are high and families may be grieving the loss of a loved one. Staying mindful about this can help with articles’ content and tone, resonate with readers, and convey the gravity of these conditions.

- Sometimes, people need a “reality check”: Occasionally those with SUD’s, AUD’s as well as family and friends need to grasp the serious nature of addiction and why seeking help and support as quickly as possible is so important. Adverts such as the one below and those used on cigarette packing can “guide” people toward recovery to avoid the outcomes, health conditions or other negative consequences of continued drug and alcohol use.

- Use all of the different types of media distribution options available: In these modern times, we have so many options available for advertising, promoting and raising awareness for causes. Options such as:

- Newspaper

- Magazine

- Radio

- Television

- Directories

- Outdoor and transit

- Direct mail, catalogues and leaflets

- Online

- Relevant specialist publications or websites

- Distribution through government, local council or healthcare services such as doctors surgeries and mental health department waiting rooms & notice boards

- And so on…

We here at Drink ‘n’ Drugs always want to help raise awareness of addiction and recovery. If you have any questions, suggestions or ideas for us to help you, we’d be only too happy to discuss this with you! You can email us at: awareness@drink-n-drugs.com

You can also find contact information for organisations, charities and groups that can help on our help & support page here.

3 thoughts on “How The Terms We Use In Addiction And Recovery Matter And How To Overcome This Vital Issue”